⬇️ Prefer to listen instead? ⬇️

- 🧫 Epithelial tissue lines many organs and acts as the body’s primary protective and interactive barrier.

- 🧪 Epithelial cells vary in shape and layering, tailored for functions like absorption, secretion, and protection.

- 🧠 Gut epithelial health connects directly to immunity and the gut-brain axis.

- 🍄 Medicinal mushrooms like Reishi and Turkey Tail can strengthen epithelial barrier integrity.

- 🩺 Disruption of epithelial tissue can lead to chronic inflammation, infection, and cancer.

Epithelial Tissue: What Is It and Why Does It Matter?

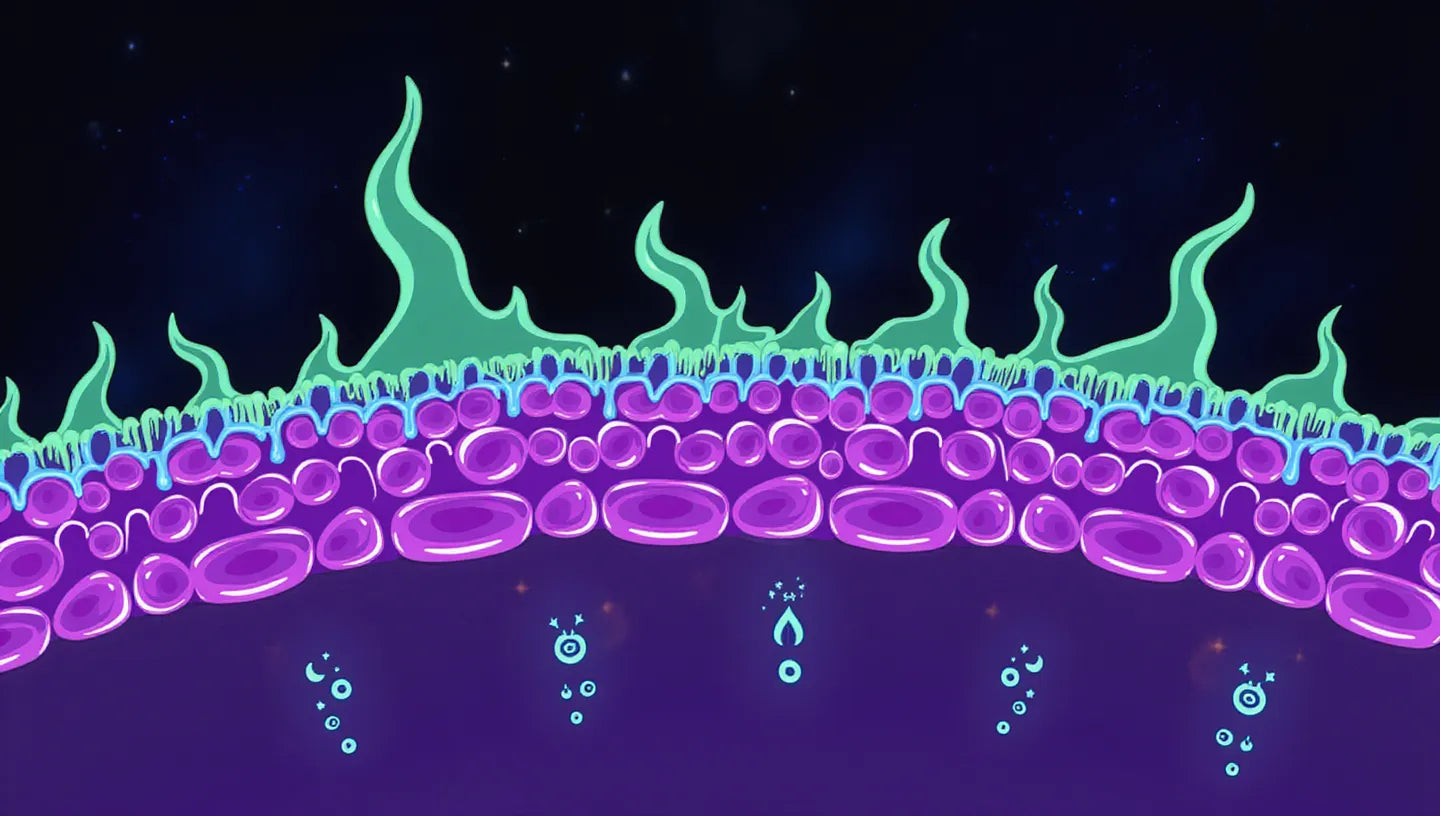

We often think about muscles or bones when we talk about our body’s structure, but epithelial tissue is the quiet guardian of your health—constantly renewing, protecting, and interacting with your environment. Found on the surfaces of your skin, lungs, gut, and more, the epithelium is the boundary between your inner world and the outside one. And, as modern research shows, its wellbeing may be influenced by things as surprising as your diet or even the mushrooms you eat.

What Is Epithelial Tissue? A Simple Breakdown

Epithelial tissue is a specialized group of closely packed cells that line the internal and external surfaces of your body. This tissue type is found nearly everywhere—covering organs, body cavities, and hollow passageways, including your digestive tract, blood vessels, and respiratory system. As a critical component of the four basic types of animal tissues—epithelial, connective, muscular, and nervous—epithelial tissue has a distinct job: it forms your body's barriers and outer layers.

These cells have a top part (apical surface) and a bottom part (basement membrane). And they connect tightly to one another through specialized junctions. This setup helps epithelial tissue do its many jobs well, especially where protection and contact with the environment are key.

Unlike other tissues, epithelial cells are avascular (they lack blood vessels), relying instead on diffusion from underlying connective tissues for nutrients. Despite this, they can also rebuild themselves very well—some epithelial tissues renew every few days to adapt to injury or environmental exposure.

Roles and Functions of Epithelial Tissue

The epithelium does more than just cover your body. It interacts, moves, and defends. Here are its five main jobs:

1. Protection

Your skin’s outermost layer, composed of stratified squamous epithelium, acts as a physical barrier against mechanical injury, harmful pathogens, UV radiation, dehydration, and chemical insults. Inside the body, epithelial layers in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts also protect against environmental chemicals and digestive enzymes.

2. Absorption

Certain areas of your body require nutrient and fluid absorption. In the small intestine, for instance, columnar epithelial cells are equipped with microvilli on their apical surfaces to maximize surface area and efficiently absorb nutrients from digested food.

3. Filtration

Some epithelial tissues specialize in selectively filtering substances out of bodily fluids. In the kidneys, simple squamous epithelial cells in the glomerulus filter blood, removing waste, toxins, and excess ions while retaining cells and large proteins.

4. Secretion

Many glands—including salivary, sweat, and endocrine glands—are composed of epithelial tissue. Glandular epithelium synthesizes and secretes hormones, enzymes, and other fluids necessary for physiological balance. For example, goblet cells within the respiratory epithelium release mucus to trap particulates and microorganisms.

5. Sensation

Sensory epithelial cells are uniquely adapted to detect external stimuli. Taste buds on the tongue and olfactory epithelium in the nose are specialized for taste and smell perception. In these cells, receptors translate chemical signals into nerve impulses for interpretation by your brain.

So, epithelial tissue is involved in almost every body process that deals with things inside and outside you. It acts as a gatekeeper or a communicator.

The 8 Major Types of Epithelial Tissue Explained

Epithelial tissue falls into several types, based on cell shape and how layers are stacked. Each type is made for a specific job. Let's look at the main forms in more detail:

A. Classification by Cell Shape

-

Squamous epithelium

These cells are thin, flat, and scale-like. Their structure allows for efficient diffusion and filtration, making them common in areas requiring quick exchange of gases or nutrients. -

Cuboidal epithelium

Roughly cube-shaped cells with centrally located nuclei, this type is typically involved in secretion and absorption. It lines glands and ducts, including those in the kidneys and pancreas. -

Columnar epithelium

Taller than they are wide, these cells are often found in the digestive tract. Their elongated shape provides space for organelles that aid in digestion and absorption.

B. Classification by Layering

-

Simple epithelium

One single layer of cells, ideal for areas where absorption, diffusion, or filtration occurs. Although efficient, it provides minimal protection. -

Stratified epithelium

Composed of multiple layers, this type provides enhanced protection. Cells continuously regenerate from the basal layer and push older cells toward the surface. -

Pseudostratified epithelium

Appears to be multi-layered due to varying cell heights and nuclei placement but is technically a single layer. Usually found in the respiratory tract, often ciliated to help move mucus and debris. -

Transitional epithelium

Found in tissues that stretch, like the bladder. These cells can change shape—flattening as the organ expands, and returning to their dome shape when the organ contracts.

Major Locations and Functions Table:

| Type of Epithelium | Key Locations | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Simple Squamous | Alveoli in lungs, blood vessels | Gas exchange, filtration |

| Simple Cuboidal | Kidney tubules, glands | Secretion, absorption |

| Simple Columnar | Digestive tract | Absorption, enzyme production |

| Stratified Squamous | Skin, oral cavity | Protection against abrasion |

| Pseudostratified Columnar | Trachea, upper respiratory tract | Mucus movement, filtration |

| Transitional | Urinary bladder, ureters | Stretch and recoil |

| Ciliated Epithelium | Trachea, fallopian tubes | Movement of substances |

This diverse lineup allows epithelial cells to meet the specific demands of various organs and organ systems.

How Epithelial Tissue Regenerates and Repairs

One of the defining characteristics of epithelial tissue is its regenerative capability. Because many epithelial cells exist in exposed regions—like the skin or gut—they undergo frequent wear and tear. To maintain functionality and prevent breaches, these tissues rely on rapid cell turnover.

For example:

- The intestinal epithelium replaces itself every 4–5 days.

- Epidermal cells of the skin undergo complete renewal every 27–30 days.

This regeneration is powered by stem cells located in the basal layer of epithelial membranes. These cells divide to produce both new stem cells (self-renewal) and differentiated cells that migrate upward or outward to replace damaged or dead cells.

During injury, epithelial tissue responds in phases:

- Inflammatory Phase: Blood clot forms, and immune cells clear debris/pathogens.

- Proliferative Phase: Epithelial stem cells generate new cells.

- Migration: Cells migrate to the wound bed, sealing the area.

- Remodeling: Tissue architecture is restored for functional integrity.

As Alberts et al. (2002) described, this system works with extraordinary speed, forming a sealed barrier in days or weeks, depending on site and severity.

Epithelial Tissue & Immunity: The Body’s First Line of Defense

Epithelial tissue is critical to innate immunity. It serves not only as a physical barrier but also as an immunologically active surface that detects pathogens and reacts swiftly.

Key functional elements include:

- Tight junctions: Protein complexes (like claudins and occludins) that prevent intercellular leakage and block microbial intrusion.

- Goblet cells: Produce mucus embedded with antimicrobial peptides, such as defensins and lysozymes.

- M cells and dendritic cells: Sample antigens and communicate with immune cells below the epithelium.

- GALT: Gut-associated lymphoid tissue consists of Peyer’s patches and immune cells that live just beneath the gut epithelium.

Remarkably, this tissue must tolerate trillions of microbes while preventing inflammation. Turner (2009) notes that the intestinal epithelium comes into contact with around 30 tons of food and roughly 100 trillion microorganisms over a lifetime. Its role in "filtering friends from foes" has implications for autoimmune disease, allergies, and chronic inflammation.

Common Conditions Affecting Epithelial Tissue

When epithelial barriers fail, the effects ripple across multiple systems:

1. Dermatological Diseases

In skin disorders like eczema, psoriasis, and acne, the stratified squamous epithelial cells are involved in abnormal growth, immune activation, or impaired keratin production—leading to dryness, inflammation, or lesions.

2. Gastrointestinal Disorders

In conditions like:

- Crohn’s Disease: Disruption causes intestinal permeability and immune overdrive.

- GERD (acid reflux): Stomach acid damages the epithelial lining of the esophagus.

- “Leaky gut” syndrome: Weakened tight junctions allow toxins and microbes to seep into the bloodstream, leading to systemic inflammation.

3. Infections

Respiratory infections (e.g., influenza, COVID-19) typically begin with microbial entry through epithelial cells of the nasal and bronchial passages. Vulnerability increases with damaged mucosal linings from pollutants or smoking.

4. Carcinomas

Most cancers begin in epithelial cells—making them carcinomas. Their high turnover rate, metabolic activity, and environmental exposure increase mutation risk. Examples include:

- Skin cancers (basal and squamous cell)

- Colon, lung, and breast carcinomas

Understanding and safeguarding epithelial integrity is increasingly seen as a public health priority.

New Frontiers: Epithelial Tissue in Medical Research

With its centrality to organ function and disease, epithelial tissue is a key focus for new research areas:

Organoids and Tissue Engineering

Scientists now grow mini-organs using epithelial stem cells to simulate real tissues. These "organoids" are used for drug testing, disease modeling, and personalized medicine. For example, intestinal organoids help researchers study inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in controlled, ethical environments.

Microbiome Research

The microbiome’s influence on epithelial behavior is groundbreaking. For instance, gut epithelial cells communicate with bacteria to modulate immunity, nutrient absorption, and mental health through the gut-brain axis.

Stem Cell Therapy

Epithelial stem cells are promising for regenerating damaged tissue—such as in burns, corneal injury, or gastrointestinal surgery. Custom-grown epithelial sheets grafted into damaged areas show how biology and new treatments can work together.

Mushroom Power and Epithelial Health: Is There a Link?

Medicinal mushrooms contain potent compounds, including beta-glucans and polysaccharides, that support epithelial tissue from both immune and structural angles.

Studies indicate:

- 🛡️ Beta-glucans bind to immune receptors like Dectin-1 on dendritic cells under epithelial layers, boosting localized immune readiness (Brown & Gordon, 2005).

- 🧬 Polysaccharides from fungal sources reduce inflammation and support epithelial resilience by enhancing tight junction proteins (Wasser, 2011).

- 🍄 Prebiotics in mushrooms act as food for beneficial microbes, which generate SCFAs like butyrate—a compound known to support epithelial repair and reduce permeability (Slavin, 2013).

Consuming mushrooms like Reishi, Shiitake, and Turkey Tail—whether grown at home in Mushroom Grow Bags or a Monotub—may offer a low-risk, high-impact way to reinforce epithelial health naturally.

How to Keep Your Epithelial Tissue Healthy

Here’s how to practice daily care of your epithelial barriers:

- 🥕 Consume Vitamins A, C, E: Vital for epithelial repair and antioxidant protection.

- 🥦 Eat fiber: Soluble and insoluble fibers feed gut bacteria that regulate epithelial signaling and inflammation.

- 💧 Stay hydrated: Keeps mucus membranes optimal for microbial clearance.

- 🚭 Avoid toxins: Smoking, heavy alcohol, and environmental pollutants damage epithelial linings.

- 🍄 Incorporate functional mushrooms: Supplements or grow kits containing beta-glucan-rich fungi offer barrier support.

Epithelial maintenance is not just about skincare—it's key to overall body health.

Vocabulary Corner: Etymology and Pronunciation Made Easy

Epithelium—from the Greek “epi” (upon) and “thele” (nipple/projection)—originally described tissues covering organs but now broadly refers to any surface-lining tissue.

Pronunciation:

- Singular: eh-puh-THEE-lee-um

- Plural: eh-puh-THEE-lee-a

Learning its roots helps understand related terms like endothelium (lining inside vessels) or neuroepithelium (nervous system interface).

A Closer Look: Microscopy and Visual Representation

Under a microscope, epithelial tissue presents orderly beauty:

- Simple squamous appears tile-like, useful for illustrating exchange surfaces.

- Columnar cells show cilia or microvilli that hint at their absorptive/transport functions.

Tools for visualization:

- Histological slides (digital or lab-based)

- Online microscopy databases

- Downloadable diagrams highlighting epithelium subclasses

These aids deepen understanding through visual learning—ideal for students, educators, or curious minds alike.

Why Epithelial Tissue Shouldn’t Be an Afterthought

Epithelial tissue lies at the heart of your body’s communication, defense, and survival systems. Whether lining your lungs, rebuilding after a cut, or fending off harmful invaders, its performance is vital to health.

By understanding the types of epithelial tissue and nourishing them with intentional habits—from nutrition to medicinal mushrooms—you reinforce the walls that keep you balanced, protected, and thriving.

Want to learn more? Read our next post on how epithelial and nervous systems interact via the gut-brain axis—or start supporting your own epithelium with our Reishi and Turkey Tail mushroom kits.

Citations

Alberts, B., Johnson, A., Lewis, J., Raff, M., Roberts, K., & Walter, P. (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Garland Science.

Turner, J. R. (2009). Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nature Reviews Immunology, 9(11), 799–809. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2653

Wasser, S. P. (2011). Current findings, future trends, and unsolved problems in studies of medicinal mushrooms. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 89(5), 1323–1332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-010-3067-4

Slavin, J. (2013). Fiber and prebiotics: mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients, 5(4), 1417–1435.

Brown, G. D., & Gordon, S. (2005). Immune recognition: A new receptor for β-glucans. Nature, 434(7030), 763.