⬇️ Prefer to listen instead? ⬇️

- 🌿 Up to 90% of a lichen’s mass is made of its fungal partner—the mycobiont (Ahmadjian, 1993).

- 🧬 Lichen partnerships often involve more than two partners, including basidiomycete yeasts found in the cortex (Spribille et al., 2016).

- ❄️ Mycobionts help lichens survive in extreme environments, including Arctic tundras and deserts.

- 🧪 Fungi from lichens are being used in pharmaceutical research for their active compounds.

- 🌍 Lichens show environmental stress well, especially from air pollution and changes in weather.

Mycobiont in Lichens: What Role Does It Play?

Lichens are some of nature’s most amazing partnerships, showing how different organisms can work closely together. The mycobiont is the fungal partner, and it plays the key role in this relationship. This partnership allows lichens to survive in some of Earth’s toughest environments. The mycobiont builds the lichen’s shape, supports nutrient exchange, and helps the whole organism withstand environmental stress. Whether you study fungi in the wild or grow related species at home in Mushroom Grow Bags or a Monotub, the role of the mycobiont highlights how essential fungi are in shaping and protecting complex biological systems.

What Is a Mycobiont?

A mycobiont is the fungus part of a lichen partnership. Most often, it comes from the Ascomycota group. This group includes most fungi that make lichens. Sometimes, fungi from the Basidiomycota group are also part of it. This is true especially in new studies where more fungi are involved.

The name “mycobiont” tells us what it is: “myco-” means fungus, and “biont” means a life form. This means lichens are not single species. Instead, they are groups of many organisms. The mycobiont helps them, and often leads them. Algae and cyanobacteria (photobionts) make food using sunlight. But, fungi in lichens are the main builders of their shape and how they work.

Unlike many fungi that live alone, lichen mycobionts usually need their partner. They cannot live in the wild without the photobiont. This need shows a long history of growing together. It has made the mycobiont very good at living in a partnership.

Mycobiont vs. Photobiont: Breaking Down the Partnership

Lichens show a common type of mutualism. But the work and benefits are not always equal. Each partner brings something very important:

-

Photobiont: Generally a green alga (e.g., Trebouxia) or a cyanobacterium (e.g., Nostoc). It makes food like sugars (carbohydrates such as glucose or ribitol). It does this by using sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water.

-

Mycobiont: It builds the physical body (or thallus) of the lichen. It keeps the photobiont safe from drying out, UV light, plant-eaters, and very hot or cold weather. And it also collects minerals from rain and the air around it.

In this division of labor, the mycobiont surrounds the photobiont with its network of hyphae. It arranges how the lichen looks inside. It also controls the lichen's outer shape. And it even decides when and how each partner divides. Some studies ask if the relationship is truly mutualistic. Or, if the fungus acts like a “controlled parasite” towards its partner that makes food.

Even with some issues, the lichen partnership has lasted and spread into many forms for over 400 million years. This shows how helpful it has been for life.

How Does Lichen Symbiosis Work?

The lichen partnership might seem simple—a fungus and an alga or cyanobacterium living together. But it involves very organized cell actions and detailed chemical talks.

Here is how it works:

-

Getting Started: The fungal spore grows and finds the right cyanobacteria or green algae. Special chemical signals then direct the physical contact.

-

Joining Together: Once they touch, the fungus starts to wrap the photobiont in special hyphal structures. This forms a layer under the lichen's surface. In many lichens, photobionts live inside cup-shaped fungal cells called haustoria. These cells help them share nutrients.

-

Resource Sharing:

- The photobiont makes sugars and oxygen using sunlight.

- The mycobiont gives structure, holds water, and protects from outside stress.

-

Growth and Reproduction: Lichens grow slowly, but they can live for tens or even hundreds of years. The mycobiont often controls how they reproduce. It does this by making fruiting bodies (apothecia or perithecia), which produce spores.

This way of working together makes lichens more like a small ecosystem than just one living thing. It is a good example of how different organisms can combine to make something bigger than what they are alone.

What Does the Fungal Partner Actually Do?

The mycobiont does most of the hard work for building and controlling the environment. Some of its key roles include:

1. Forming the Thallus

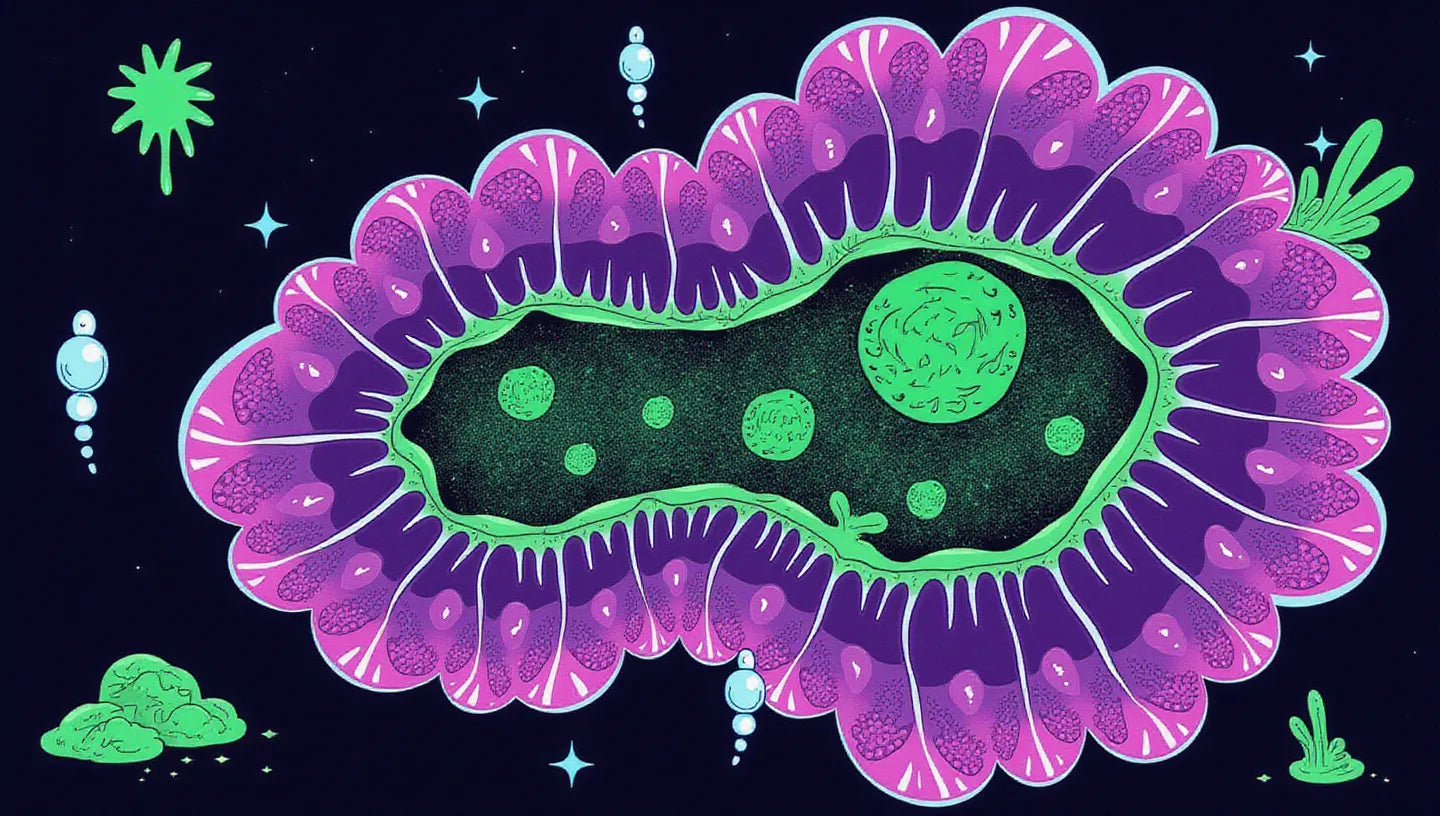

The thallus is most of the lichen's body. Fungal hyphae build almost all of it. These tangled threads twist and join, making layers like:

- Cortex (outer protective skin)

- Photobiont layer

- Medulla (a loose inner layer aiding in water storage)

- Attachment structures (e.g., rhizines)

Each layer helps protect, gather light, and move water and nutrients well.

2. Managing Water and Nutrients

The mycobiont is like a sponge in nature. It soaks up rain, dew, and dust from the air. Many lichens do not grow directly in soil. So, it is very important for them to take in nutrients from the air. The fungal part holds water. This makes water available to the photobiont even when it is dry.

3. Chemical Defense and UV Protection

Many mycobionts make chemicals like melanin, parietin, or usnic acid. These chemicals:

- Block harmful UV rays

- Discourage plant-eaters and disease-causing germs

- Function as antioxidants

These features are key for living in open places.

4. Anchoring and Adherence

The fungal partner attaches the lichen to bark, rock, soil, or man-made surfaces. It does this through structures like rhizines or holdfasts. This anchoring is not just for structure. It also stops wind from wearing them away. And it helps them spread to new places.

Environmental Toughness: Mycobionts in Extreme Environments

Lichens can be found in places as barren as Antarctic rocks, high mountain cliffs, and sun-baked deserts. The main reason for this toughness is how well the mycobiont can change:

- Changing Hyphae: Fungal hyphae can change their shape. This helps them hold more water or make thicker coverings when they need to.

- Sleeping and Waking: When it is dry or frozen, both partners go into a sleep-like state. They start working again only when moisture comes back.

- Keeping Temperature Steady: The mycobiont’s structure slows down fast temperature changes. This keeps the weak photobiont safe from sudden heat or cold.

Studies in astrobiology even tested lichens in conditions like Mars' surface, with low pressure. They lived. This was largely because of their fungal structure.

Not Just One Fungus: How Lichen Partners are Complex

For many years, people thought lichens had only two partners. This idea changed with important research by Spribille et al. (2016). They found a third fungal partner. It was a basidiomycete yeast that no one had seen before, inside the lichen cortex.

This finding showed a three-part (or even many-part) partnership:

- Ascomycete mycobiont

- Algal or cyanobacterial photobiont

- Basidiomycetous yeast

Now, researchers think this multi-partner setup might be common, not rare. These findings suggest lichens are more like groups of microbes working together than just two simple partners. This complexity shows advanced ways microbes control things. And it may explain why lichens have so many different shapes and chemical makeups.

Grouping & Types of Lichens with Mycobionts

The lichen's physical shape is mostly decided by what kind of fungal partner it has. Groups include:

- Crustose: These are compact, crust-like shapes that stick tightly to surfaces.

- Foliose: These look like leaves with lobes; they are generally attached loosely.

- Fruticose: These are branched or shrub-like, often hanging down or standing up.

Nash (2008) said that people usually group lichens by the mycobiont's family, not the algae's. This shows how important the fungus is to its identity.

Knowing these types helps with:

- Checking the environment

- Naming them in nature

- Seeing how many different life forms there are when the environment changes

The Role of Mycobionts in a Healthy Environment

The mycobiont helps keep things steady. Because of this, lichens do very important things for the environment:

- Making Soil: Lichens break down rocks with chemicals. This starts the first stage of growth in places like mountain slopes or old lava fields.

- Getting Nitrogen: Lichens that partner with cyanobacteria can take nitrogen from the air. The fungal structure helps them do this. This adds nutrients to places that do not have much.

- Air Quality Monitoring: Lichens react to sulfur dioxide, ozone, and heavy metals. If certain lichen types disappear, it can be an early sign of pollution or weather stress.

In these roles, lichens show changes in the environment early. And the mycobiont makes sure they stay strong in their body and chemistry.

Lichens and the Mushroom Grower: Why Should You Care?

You might grow fancy mushrooms or fungi that help plants. Even then, you should see what mycobionts can teach you:

- Complex Partnerships: Mycobionts are like mycorrhizal fungi. They show how powerful it is for living things to change their way of life through mutualism.

- Toughness: Lichen fungi show they can handle very harsh conditions. They can be models for things like materials that copy nature or crops that can stand up to weather changes.

- Finding New Uses: Fungi from lichens have active chemicals. These are different from chemicals found in fungi that eat dead things or cause disease.

Simply put, learning about lichen partnerships helps you better understand what fungi can do. They can be food, medicine, and friends to the environment.

Misconceptions About Lichens and Fungi

It is important to correct common false ideas about lichens and fungi for anyone who studies them.

- Lichens are not plants or mosses—they are mixed living things.

- The fungal partner makes up to 90% of the lichen's total weight (Ahmadjian, 1993).

- Many people do not know that lichens do not grow from seeds or work like plants with stems and leaves.

Putting lichens in the fungal kingdom helps us understand them correctly in terms of their environment, how they are named, and how they work.

Can You Grow a Lichen? (And Why It’s So Challenging)

Unlike mushrooms, it is hard to grow lichens in labs or greenhouses. This is hard because of:

- The partners need to match each other exactly.

- Their very slow growth—just a few millimeters per year.

- It is hard to make them reproduce or have normal body processes outside their small natural homes.

Growing mycelium for mushrooms is simple. But lichens need you to keep a whole small ecosystem alive at once. This is much harder.

Interesting Species: Some Examples of Lichen Mycobionts

Here are some different lichens that have mycobionts:

- Cladonia rangiferina (Reindeer lichen): A main food for reindeer in the Arctic.

- Xanthoria parietina: You can find this on walls and trees. Its bright orange body has parietin, which helps protect it from the sun.

- Usnea spp. (Old Man’s Beard): Known for fighting germs; often used in natural medicine.

These examples show how one fungal partner can lead to very different ways of life and looks.

Lichens in Science and Medicine: What Fungi Give Us

Mycobionts do more than just help the environment. They also have promise for technology:

- Medicine: Lichen fungi make special chemicals called polyketides and depsides. These can fight germs or reduce swelling.

- Watching Pollution: Chemicals from mycobionts help track past pollution in different areas.

- Natural Materials: The strong structure of lichens might give ideas for materials that break down naturally. These could be used in building or clothes.

As science learns more about how fungi work and their chemicals, mycobionts might become strong tools for new, lasting ideas.

The Unnoticed Ruler of Lichen Partnerships

Lichens are wonderfully complex. In them, the mycobiont is still the unnoticed ruler. It forms the body, guides the partnership, and keeps them alive in places where few other things can go.

If you want to study fungi, ecology, or grow mushrooms, learning about what fungal partners do in lichen partnerships helps you better value how clever and tough fungi are. You might be looking at the inside of a mushroom or checking a rock for signs of life. Either way, you are interacting with a world that fungi always shape.

Citations

- Ahmadjian, V. (1993). The Lichen Symbiosis. John Wiley & Sons.

- Honegger, R. (2008). Mycobionts in lichen symbioses form the structural matrix and dominate the relationship. Symbiosis, 45(1), 65–87.

- Nash, T. H. (2008). Lichen Biology (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Spribille, T., Tuovinen, V., Resl, P., Vanderpool, D., Wolinski, H., Aime, M. C., ... & McCutcheon, J. P. (2016). Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens. Science, 353(6298), 488–492.